Author: Zenia A. Babool

November 13, 2025

Author’s Note

I remember waking up at 6 A.M. to wash off the oily residue of topical creams, the headache after cortisone shots, and the pile of Paw Patrol and Hello Kitty stickers that I collected from the front desk of dermatology clinics. I was diagnosed with alopecia areata (a subtype of alopecia) as an infant, and it guided my upbringing and my current life in ways that I’m still understanding. My story is just one of millions. Some people are diagnosed with alopecia at birth, others as teenagers, and many as adults, facing the pressures of balancing their professional and familial lives. Some people have patches that come and go, while others experience complete hair loss. Some have treatments that are effective quickly, while others experience therapy after treatment with limited success. The bottom line is that each journey is different and unique, and my research shows one common thread behind each story: regardless of age at diagnosis, severity, or treatment procured, alopecia consistently impacts the psychological well-being of patients. This paper acknowledges that while treatment for alopecia continues to advance, we must recognize that every patient with alopecia deserves care that prioritizes both physical and psychological aspects of their condition.

Introduction

Alopecia covers a variety of conditions characterized by hair loss in areas where hair typically grows. Clinically, alopecia is formally classified into non-scarring (where hair is lost but follicles remain intact and regrowth is possible) and scarring (cicatricial) that involves permanent follicular ruination. To accurately diagnose alopecia, a detailed clinical history and assessment using devices such as trichoscopy are essential to creating an effective treatment plan (Russo et al., 2023). Given that alopecia can be unpredictable, very destructive, and affects many patients across the world, there is a need for new, better, and complete assessments. Today, new research increasingly suggests a link between alopecia and neuroimmune interactions, with an equally strong emphasis on psychodermatological phenomena (Wang et al., 2022).

Review Objective

The key focus of this review is to (1) classify various alopecia types and their symptoms, (2) discover their etiological and pathophysiological supports, (3) review current diagnostic frameworks, (4) analyze treatment mechanisms and implications, (5) examine the relationship between alopecia and patient’s emotional and psychological states, and (6) identify methodological gaps to improve patient welfare.

Diagnosis and Classification

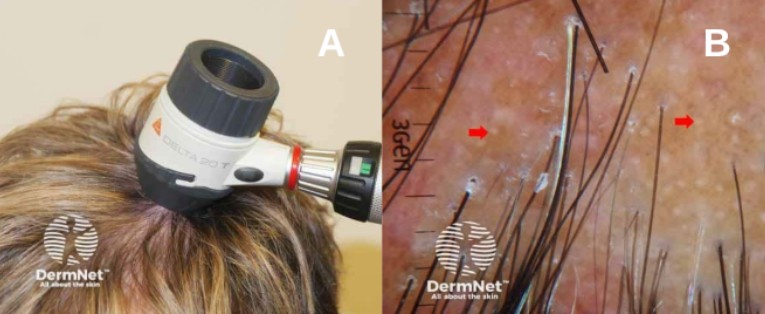

Alopecia diagnosis combines comprehensive patient history, clinical examination, and trichoscopy, a non-intrusive method that has revolutionized scalp assessments. By using trichoscopy, clinical examiners can identify features specific to alopecia areata (exclamation-point hairs and yellow dots), androgenetic alopecia (anisotrichosis and perifollicular pigmentation), and telogen effluvium (empty follicles) (Figure 1A and 1B). Trichoscopy also helps clinicians distinguish conditions by examining the sensitivity and specificity in Alopecia Areata (94% and 92%), in Androgenetic Alopecia (91% and 89%), and in TE (86% and 84%), respectively (Russo et al., 2023) (Figure 2A and 2B). Trichoscopy particularly improves diagnostic ability and precision because it reduces the need for invasive biopsy procedures. Still, however, biopsies remain essential in confirming indistinguishable forms of non-scarring and scarring alopecia. Histopathology, another diagnostic tool that can examine features such as fibrotic changes in central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia or perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrates in lichen planopilaris (see the scarring alopecia section further down), is crucial in guiding identification and intervention strategies.

Figure 1. Trichoscopy in alopecia areata diagnosis. (A) Dermatoscope positioned on scalp for non-invasive trichoscopic examination. (B) Trichoscopic view of alopecia areata, showing characteristic yellow dots (red arrows) that represent empty hair follicles and sebaceous glands visible at the follicular openings. Images sourced from DermNet.

Non-Scarring Alopecia

Non-scarring alopecia preserves follicular integrity, making regrowth possible; however, this category encompasses a diverse range of types with distinct etiologies (Figure 2).

- Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA): a hormone-driven condition resulting from follicle sensitivity to dihydrotestosterone. Thinning in males is best seen at the temples and crown, whereas thinning in women starts at the vertex. Clinically, AGA is characterized by anisotrichosis (texture variation) and hair shaft miniaturization on trichoscopy (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

- Alopecia Areata (AA): An autoimmune disorder that attacks hair follicles, creating patchy hair loss. AA affects 2% of the global population, with variation by region. Lifetime prevalence estimates are around 0.10% overall, with a higher prevalence in adults (~0.12%) and a lower prevalence in children (~0.03%) (Jeon et al., 2024). Globally, incidence and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) have increased by 49% between 1990 and 2019, particularly in low socio-demographic regions. AA can be treated, but recurrence is common (Wang et al., 2022).

- Telogen Effluvium (TE): TE is triggered by physiological stressors (i.e., illness, surgery, or hormonal changes), leading to hair shedding about three months after an inciting event. Classification and diagnosis are reliant on timing, trichogram (microscopic examination of plucked hair), or biopsies, which show increasing telogen hair proportions with minor inflammation (Cleveland Clinic, 2025).

- Anagen Effluvium: Induced by toxic exposure or chemotherapy, causing rapid hair loss during the hair’s growth phase, which can compromise regrowth if treatments persist (Amarillo et al., 2022).

- Traction Alopecia: Chronic tension usually from tight hairstyles that can cause hair loss; when detected early, follicles remain alive, but lengthened traction can cause permanent damage (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

- Trichotillomania: A psychiatric disorder classified by compulsive hair pulling (usually in relation to stress), resulting in patchy hair loss, broken follicles, and potential scarring (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

- Alopecia Syphilitica: A product of secondary syphilis that causes “moth-eaten” hair loss patterns but can be resolved with treatment of the underlying infection (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Clinical presentations of non-scarring alopecia subtypes. (A) Androgenetic alopecia in a female patient showing diffuse thinning and reduced hair density at the vertex with preservation of the frontal hairline. (B) Alopecia areata presents as a well-demarcated, round patch of complete hair loss on the scalp. (C) Traction alopecia affecting the temporal and frontal hairline, characterized by hair loss in areas of chronic mechanical tension from tight hairstyling. (D) Androgenetic alopecia in an older female patient with advanced diffuse thinning across the crown and vertex, demonstrating visible scalp and miniaturized hair follicles. All images sourced from DermNet.

Scarring/Cicatricial Alopecia

Hair follicles are permanently damaged in these types, making hair loss irreversible. Common subtypes include:

- Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA): A condition displayed in many postmenopausal women that can be characterized by continued hairline recession and eyebrow thinning (Figure 3). It presents itself with perifollicular erythema and tenuous inflammation (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

- Lichen Planopilaris (LPP): An autoimmune-mediated form of alopecia that causes perifollicular scaling, itching, and redness manifested in follicular destruction that can result in permanent hair loss (Al Aboud et al., 2024).

- Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia (CCCA): Hair loss begins at the central scalp and spreads outwards due to inflammation that causes follicular destruction and scarring (Al Aboud et al., 2024). The majority of cases are seen in women of African descent.

Figure 3. Clinical presentation of frontal fibrosing alopecia. Progressive hairline recession along the frontal and temporal margins with characteristic perifollicular erythema and loss of vellus hairs, typical of scarring alopecia in postmenopausal women. Image sourced from DermNet.

Prevalence and Significance

In the United States alone, 50 million men and 30 million women are affected by AGA- making it the most common type of hair loss (Gupta et al., 2025). Once men and women reach the age of 50 or above, 50% of men and 40% of women exhibit signs of androgen-dependent hair thinning (Gupta et al., 2025). Similarly, AA affects over 160 million people worldwide, with an individual lifetime risk of approximately 2% (American Hair Loss Association, 2023). Data from the Global Burden of Disease expose that although age-standardized rates of AA have remained stable or declined slightly, the absolute number of cases and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) associated with AA have significantly increased by 49% from 1990 to 2019, specifically in lower socio-demographic regions (Wang et al., 2022; Ding et al., 2025). These valuable statistics indicate the extended global impact of alopecia on both an individual and a public scale.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

AA is driven by autoimmune systems where cytotoxic T-cell infiltration stops hair follicle immune privilege, a mechanism influenced by genetic vulnerabilities in the immune-regulatory loci region (Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, AGA is guided by genetic susceptibilities and androgen sensitivity, particularly dihydrotestosterone (DHT), leading to damaged hair growth cycles and follicular thinning (Al Aboud et al., 2024). In telogen effluvium, systemic stressors, such as illness or hormonal changes, can trigger premature modification of hair follicles into the resting phase. Traction alopecia and trichotillomania are caused by mechanical and behavioral etiologies, respectively, while alopecia syphilitica is rooted in follicular colonization by Treponema Pallidum (Cleveland Clinic, 2025).

Treatment Options and Mechanisms

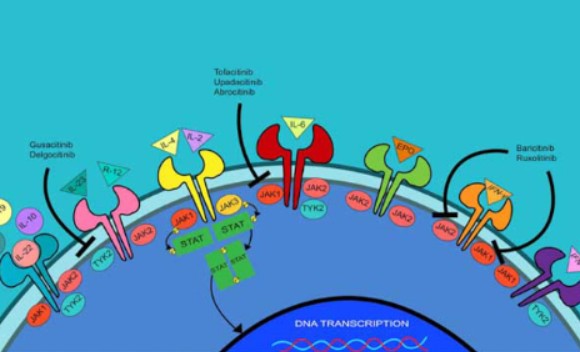

Treatment strategies vary depending on the type of alopecia and rely on evidence-based therapeutic approaches. In AA, intralesional corticosteroids remain the primary and most effective treatment option, achieving hair regrowth in over 60% of patients (Yee et al., 2020). JAK inhibitors such as baricitinib (Olumiant) and deuruxolitinib (Leqselvi) result in a shift towards decreased Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) scores when compared with placebos, indicating quantifiable hair regrowth (Nestor et al., 2021) (Figure 4). In AGA, topical minoxidil promotes regrowth in approximately 40% of men by extending the anagen phase of the hair cycle and acting as a potassium channel opener to stimulate hair follicle cell growth. Similarly, in AGA, finasteride acts as an inhibitor of 5α-reductase, allowing the hair growth cycle to stabilize and improve hair count in up to 90% of treated men (Nestor et al., 2021). A recent study conducted by Cruciani et al., non-pharmacological methods, such as PRP injections, indicate variable effectiveness in analyzing modest hair density growth; however, more rigorous trials are necessary to standardize treatment (Cruciani et al., 2021).

Nutrition and gut-mediated pathways have also been highlighted as correlating factors in alopecia. There is quantifiable evidence that vitamin and mineral deficiencies are associated with higher rates of non-scarring alopecia. Specifically, low serum ferritin levels were reported in 59% of women with chronic telogen effluvium, zinc deficiency in 21% of patients with AA, and vitamin D deficiency in 91% of AA cases (Almohanna et al., 2019). Broader dietary interventions also influence alopecia. Protein supplements can improve hair integrity and tensile strength, omega-3 fatty acids can reduce hair follicle inflammation, and low-glycemic diets have been correlated with reduced androgen-driven miniaturization in androgenetic alopecia (Pham et al., 2020). Recent studies have also suggested that gut-skin axis dysbiosis is responsible for inflammation in immune pathways relevant to AA, with probiotic interventions demonstrating clinical improvements in subsets of patients (Mahmud et al., 2022).

Beyond pharmacological and nutritional strategies, cosmetic and technological approaches have been investigated as methods for alopecia treatment. Recent surveys indicate that patients can achieve effective regrowth through hair cosmetics, such as conditioners, serums, and camouflage fibers, which improve hair shaft strength, reduce breakage, and enhance patient satisfaction, particularly among women diagnosed with telogen effluvium and androgenetic alopecia (Dias et al., 2021). Adherence to treatment types also plays a significant role in alopecia outcomes. Nestor et al. reported that over 30% of patients discontinue therapy due to perceived inefficiency or financial burden, highlighting the importance of consistency and cost considerations in long-term disease management. Advancements in drug delivery through nanoparticle-based systems have increased the follicular penetration of active compounds, reducing the side effects of many treatment options and improving patient safety and drug efficacy (Raszewska-Famielec & Flieger, 2022). Nanoparticle formations of minoxidil and finasteride improve tolerability and bioavailability compared to standard topical treatments, representing an emerging technology that can improve clinical outcomes and the quality of life for patients with alopecia.

Figure 4. JAK-STAT Signaling Pathway and Therapeutic Targets in Alopecia Areata. Schematic illustration showing the mechanism of action of JAK inhibitors in blocking the JAK-STAT pathway, which is implicated in the autoimmune pathogenesis of alopecia areata. Various cytokine receptors activate JAK proteins, which trigger STAT-mediated DNA transcription. JAK inhibitors interrupt this cascade to reduce autoimmune follicle attack. Image sourced from DermNet.

Psychological and Emotional Burden

Hair health has a significant impact on psychological well-being, particularly among adolescents and women. AA patients face elevated rates of anxiety and depression (30–38% and 50%, respectively), and impaired quality of life is well documented across alopecia subtypes (Macbeth et al., 2022). In children, social isolation and reduced self-esteem are documented, heightening the need for integrated psychological support. Comparisons to chronic systemic diseases exemplify the profound psychological impact of alopecia (Wang et al., 2022). A strong correlation has been found between the psychological well-being of the human brain and hair health, particularly among adolescents and women. In children, reduced self-esteem and social isolation have been documented, heightening the necessity for psychological support (Wang et al., 2022). Psychological stress has been linked to the pathogenesis of AA, where the activation of autoimmune and apoptotic pathways disrupts hair follicle immunity and accelerates follicular degeneration (Ahn et al., 2023). This reinforces the heightened clinical burden, as up to 50% of AA patients reported significant distress, including poor self-esteem and impaired social functioning (Hunt, 2022).

Clinical Gaps and Future Directions

Despite current advances in diagnosis and treatment of alopecia, there remains a profound number of clinical gaps. In cicatricial alopecia, diagnosis ambiguity remains a barrier, and in alopecia areata, treatment relapses are common, with over 63% of patients relapsing within a year after medical treatment (Al Aboud et al., 2024). The long-term effects and efficiency of JAK inhibitors are still under investigation, while other therapies, such as PRP, lack standardized protocols. There is a clear absence of definitive biomarkers for alopecia therapy, particularly in the intersection of genetic findings and individualized medical plans. Nutritional and dietary connections remain limited due to the lack of large-scale trials, hindering the development of clear guidelines for diets targeting deficiencies or supplement consumption. Cosmetic approaches and delivery platforms demonstrate early benefits but require long-term validation of safety and efficacy. Alopecia patients are prone to pressures such as anxiety, depression, and a reduced quality of life, making it important for treatment plans to address patient lifestyle before prescribing treatment. These gaps will require biomarker-driven research, standardized protocols for therapies, and an integration of nutritional and psychological care for patients with alopecia.

Conclusion

Alopecia underscores a complex, intertwined web of biological, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Future progress depends on refining therapies and building personalized treatment plans that incorporate genetics, nutrition, and mental health support. Innovations in biomarker discovery, targeted drug delivery, and preventive strategies can transform management, while integrative care models can better address the holistic needs of patients. Research, accessibility, and individualized treatment can shift from managing alopecia to truly improving outcomes and quality of life for those affected.

Terms & Abbreviations – Quick Reference

AA – Alopecia Areata: Autoimmune patchy hair loss.

AGA – Androgenetic Alopecia: Male or female pattern hair loss caused by DHT sensitivity.

Anagen Effluvium – Rapid hair loss during the growth phase, often from chemotherapy.

Anisotrichosis – Variation in hair shaft thickness

Alopecia Syphilitica – Hair loss from secondary syphilis infection.

CCCA – Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia: Scarring alopecia starting at the central scalp, common in women of African descent.

DALYs – Disability-Adjusted Life Years: Measure of disease burden from illness or disability.

DHT – Dihydrotestosterone: Hormone contributing to follicle miniaturization in AGA.

FFA – Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia: Scarring alopecia affecting the hairline and eyebrows, mostly in postmenopausal women.

Immune Privilege – A Mechanism by which hair follicles normally avoid immune attack.

JAK Inhibitors – Drugs that block Janus kinase pathways to reduce autoimmune hair follicle attack.

LPP – Lichen Planopilaris: Autoimmune scarring alopecia with inflammation and permanent follicle loss. PRP – Platelet-Rich Plasma: Therapy using concentrated platelets to stimulate hair regrowth.

SALT – Severity of Alopecia Tool: Scoring system for the extent of hair loss in AA.

SDI – Socio-Demographic Index: Global measure of a region’s income, education, and fertility.

TE – Telogen Effluvium: Temporary hair shedding due to stress or systemic changes.

Traction Alopecia – Hair loss caused by chronic pulling or tension.

Treponema pallidum – A bacterium that causes syphilis

Trichotillomania – Compulsive hair-pulling disorder.

Trichoscopy – Non-invasive scalp examination for hair loss patterns and follicle assessment.

Sources

Ahn, D., Kim, H., Lee, B., & Hahm, D. H. (2023). Psychological stress-induced pathogenesis of alopecia areata: Autoimmune and apoptotic pathways. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(14), Article 11711. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241411711

Al Aboud, A. M., Syed, H. A., & Zito, P. M. (2024, February 26). Alopecia. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538178/

Almohanna, H. M., Ahmed, A. A., Tsatalis, J. P., & Tosti, A. (2019). The role of vitamins and minerals in hair loss: A review. Dermatology and Therapy, 9(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-018-0278-6

Amarillo, D., de Boni, D., & Cuello, M. (2022). Chemotherapy, alopecia, and scalp cooling systems. Actas Dermosifiliográficas, 113(3), 278–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2021.09.003

American Hair Loss Association. (2023, August 14). POLL: What percentage of people worldwide will experience alopecia in their lifetime? Dermatology Times. https://www.dermatologytimes.com

Cleveland Clinic. (2025). Telogen effluvium. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/telogen-effluvium

Cruciani, M., Masiello, F., Pati, I., Marano, G., Pupella, S., & De Angelis, V. (2021). Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Dermatology, 61(7), 815-827. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34967722/

DermNet. (n.d.). DermNet NZ – All about the skin | DermNet NZ. Dermnetnz.org. https://dermnetnz.org/

Dias, M. F. R. G., Loures, A. F., & Ekelem, C. (2021). Hair cosmetics for the hair loss patient. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 54(4), 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1739241

Ding, H., Yu, Z., Yao, H., Xu, X., Liu, Y., & Chen, M. (2025). Global burden of alopecia areata from 1990 to 2019 and emerging treatment trends analyzed through GBD 2019 and bibliometric data. Scientific Reports, 15, Article 25869. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07224-x

Gupta, A. K., Wang, T., & Economopoulos, V. (2025). Epidemiological landscape of androgenetic alopecia in the US: An All of Us cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 20(2), Article e0319040. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0319040

Hunt, N. (2022). Identity and psychological distress in alopecia areata. British Journal of Dermatology, 187(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21597

Jeon, J. J., Jung, S.-W., Kim, Y. H., Parisi, R., Lee, J. Y., Kim, M. H., Lee, W.-S., & Lee, S. (2024). Global, regional and national epidemiology of alopecia areata: A systematic review and modelling study. British Journal of Dermatology, 191(3), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjd/ljae058

Macbeth, A. E., Holmes, S., Harries, M., Chiu, W. S., Tziotzios, C., de Lusignan, S., Recke, A., Naldi, L., Ormerod, A. D., Torres, T., & Chalmers, J. (2022). The associated burden of mental health conditions in alopecia areata: A population-based study in UK primary care. British Journal of Dermatology, 187(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21055

Mahmud, M. R., Akter, S., Tamanna, S. K., Mazumder, L., Esti, I. Z., Banerjee, S., Akter, S., Hasan, M. R., Acharjee, M., Hossain, M. S., & Pirttilä, A. M. (2022). Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: Gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes, 14(1), Article 2096995. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2096995

Management of androgenetic alopecia in men in 2025. (2025). Canadian Dermatology Today.https://canadiandermatologytoday.com

Nestor, M. S., Ablon, G., Gade, A., Han, H., & Fischer, D. L. (2021). Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 20(12), 3759–3781. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14537

Oaku, Y., Abe, A., Sasano, Y., Sasaki, F., Kubota, C., Yamamoto, N., Nagahama, T., & Nagai, N. (2022). Minoxidil nanoparticles targeting hair follicles enhance hair growth in C57BL/6 mice. Pharmaceutics, 14(5), Article 947. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14050947

Pham, C. T., Romero, K., Almohanna, H. M., Griggs, J., Ahmed, A., & Tosti, A. (2020). The role of diet as an adjuvant treatment in scarring and nonscarring alopecia. Skin Appendage Disorders, 6(2), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1159/000504786

Raszewska-Famielec, M., & Flieger, J. (2022). Nanoparticles for topical application in the treatment of skin dysfunctions—An overview of dermo-cosmetic and dermatological products. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(24), Article 15980. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232415980

Russo, G., et al. (2023). Diagnostic accuracy of trichoscopy in common forms of alopecia. British Journal of Dermatology. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.21850

Verywell Health. (2025, August). What is alopecia areata? Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com

Wang, H., Pan, L., & Wu, Y. (2022). Epidemiological trends in alopecia areata at the global, regional, and national levels. Frontiers in Immunology, 13, Article 874677. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.874677

Yee, B. E., Tong, Y., Goldenberg, A., & Hata, T. (2020). Efficacy of different concentrations of intralesional triamcinolone acetonide for alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 82(4), 1018–1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2019.11.066